Ditko’s successor John Romita streamlined the eyes, creating a more mysterious look to the character, and loosened the suit’s webbing, if for no other reason than it was easier and quicker to pencil, an important factor to consider when one has to complete twenty plus pages of art in two weeks to keep the deadlines of a monthly comic book. Romita retained the diaphanous under-the-arm webbing, but as he continued to pencil Spidey’s adventures, this web membrane appeared less and less until it disappeared entirely. Most people, even avid fans, don’t remember its ever being a part of the suit.

It wasn’t long before Romita’s interpretation became standard. In fact, Romita himself—who served as Marvel’s in-house artistic director for many years after retiring from monthly penciling duties—designed the original costume that the personal appearance Spideys wore. It tickled me to think I was wearing a “Romita,” the way celebrities gush over donning a “Dior” or “Armani” on the red carpet.

Beginning with issue #298 in early 1988, in a controversial move by then Amazing Spider-Man Editor Jim Salicrup, a new young artist Todd McFarlane—previously creating a sensation with his penciling on the Incredible Hulk—was assigned to the title. Fans immediately took to McFarlane’s highly stylized, somewhat “cartoony” design of the Web-Swinger and McFarlane became an overnight sensation. His impact on Spider-Man was such that it broke into the mass media. The artist’s name was even used as an answer on an episode of Jeopardy.

Ironically, although viewed by some as a bastardization of the character and by all as a totally new look for the Web-Spinner, McFarlane’s Spidey owed much to Ditko albeit a highly exaggerated interpretation of the hero’s original artist. McFarlane’s webbing design was similarly tighter and busier, and he drew his eyes bigger, à la Ditko. He also made the Web-Head’s moves creepier by exaggerating them, making them more angular, as if performed by a contortionist, much the same way as Ditko. In fact, it was Ditko’s take on Spider-Man that inspired my performance of the hero.

McFarlane’s style was like Ditko on acid. Beyond revamping these aforementioned traditional elements of the suit, he also redesigned the character’s chest icon and the look of the webbing when it shot from Spider-Man’s Web-Shooters. The spider chest icon, for the entire life of the character to that point, was drawn less representational, more like a child’s conception of the arthropod. McFarlane’s was still economic, as symbols should be, but more realistic. McFarlane’s webbing—when shot—detailed the strands as they projected, presenting them as entwining to create a single super strong strand. It was impressive, but a headache for all those that followed to emulate.

McFarlane’s popularity made my appearances more difficult. I was frequently asked, “Why are your eyes so little?” Some of the more confrontational fans challenged with “You’re not Spider-Man. Your eyes are too small.” I’d remain unperturbed and counter with “You must be referring to that McFarlane guy’s wild interpretation of me in the comics,” but the “eye” attacks only increased while my patience decreased.

By 1993, McFarlane’s design for the Web-Slinger became the standard, and the Marvel Mucky-Mucks decided that the design of the costume should be updated to reflect the change. It only took them a half-decade, which is only a few months in corporate bigwig years.

For a department with little to zero budget, this was a big deal. Bigger still was the woman they hired to create the redesign. I did not know Betty Williams, nor had I ever heard of her, but she was a legend in New York theater circles. Her costume work on the Great White Way spanned more than four decades and included the costumes for the original productions of The Fantasticks, The Boys in the Band and Oh, Calcutta (Quite an accomplishment when one considers that the show featured extended scenes of total nudity). She also worked extensively with New York City Opera, Alvin Ailey Dance Company and New York Shakespeare Festival.

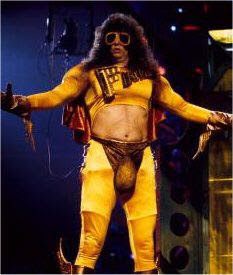

I knew none of this when I entered her second floor studio on Seventh Avenue in Manhattan’s garment district to test the new suit. The space was vast; it appeared to be a single room—nearly the entire floor—flanked on three sides by floor-to-ceiling windows. Yet, it was still dark. What little light there was came from the occasional fluorescent light fixture and a smattering of desk lamps at the sewing-machine stations. I half-expected to hear the buzzing of a bulb. Swatches of fabric were strewn around the room; on desks, tables, hanging off of lamps, window sills and across the floor. It looked like a legion of harlequins and tatterdemalions did battle with neither side proving the victor. Leaning against the one windowless wall stood bolts of fabric of every shade and pattern. In the intermittent areas between the windows and directly along the left wall of the entrance were corkboards covered with sketches of the latest projects Williams and her team were working on. Turn-of-the-century French gowns rubbed against 20s flapper dresses which fought for cork with Victorian gentlemen. But one design instantly caught my attention: Howard Stern as his ignoble gaseous guardian of good, Fartman!

I knew none of this when I entered her second floor studio on Seventh Avenue in Manhattan’s garment district to test the new suit. The space was vast; it appeared to be a single room—nearly the entire floor—flanked on three sides by floor-to-ceiling windows. Yet, it was still dark. What little light there was came from the occasional fluorescent light fixture and a smattering of desk lamps at the sewing-machine stations. I half-expected to hear the buzzing of a bulb. Swatches of fabric were strewn around the room; on desks, tables, hanging off of lamps, window sills and across the floor. It looked like a legion of harlequins and tatterdemalions did battle with neither side proving the victor. Leaning against the one windowless wall stood bolts of fabric of every shade and pattern. In the intermittent areas between the windows and directly along the left wall of the entrance were corkboards covered with sketches of the latest projects Williams and her team were working on. Turn-of-the-century French gowns rubbed against 20s flapper dresses which fought for cork with Victorian gentlemen. But one design instantly caught my attention: Howard Stern as his ignoble gaseous guardian of good, Fartman!It was love at first sight. The place screamed creativity, and I figured anyone who ran this Disneyland of design must be a lovably eccentric creative genius. How could she not be? She created the Fartman costume!

I was not disappointed.

Betty Williams was a diminutive elderly woman who looked like a cross between Woody Allen and Bea Arthur, or Edna Mode—the superhero seamstress from The Incredibles—only with gray hair and wrinkles. Her hair looked like she went to the same hair stylist as Moe Howard of the Three Stooges. An off-white work apron—that looked as if she hadn’t taken it off in half a century—covered a short black dress. Around her neck hung a golden-yellow tape measure; behind her ear was a red wax pencil. She had crows’ feet around her lips often indicative of people who smoked three packs a day since grade school, though she didn’t reek of smoke. She had sharp steely eyes that said, “I’ve been around some, so don’t f*** with me!” a look that only one who’s dealt with hundreds—perhaps thousands—of actors during numerous costume fittings spanning more than sixty years can achieve. When it comes to fittings, actors are like children getting cleaned and dressed for church: they whine, fidget, bitch, moan, and ask, “Are we done, yet?” every five minutes. It’s a scenario perfectly exemplified in Mike Leigh’s Topsy-Turvy, which, despite its antiquity, has not changed one iota since Gilbert and Sullivan were Sultans of the Savoy in London, circa 1900.

This was not to suggest Williams was a witch. Hardly. Though her mien was stoic. There was a sparkle behind her eyes and an affection in her demeanor that could only come from someone who still loved what they did. She just didn’t suffer fools, or actors, lightly. The stage may be their milieu, but here, in her workshop, she was Queen, i.e. Leave your ego at the door and let me do my job.

She handed me the newly-designed threads, or webs, as the case may be, and waited. There was no need for her to say “Drop your drawers. I haven’t got all day!” She respected that I was a professional and expected my feelings toward her to be mutual. There is no room for humility on the part of the actor during fittings, just as there isn’t any tolerance for salaciousness by the costumer. I had no problem stripping in front of Williams. I’d done my fair share of baring myself, not only in fittings before countless other Betty Williams’s of school and summer theater productions, but also offstage in front of cast and crew members. Williams was as interested in seeing my naked body as a sister or brother espying his or her nude sibling is. Contrarily, my boss, when she realized that I wasn’t going to retreat to the bathroom to try on the new suit, blurted, “You’re going to change here?!!” Williams and I exchange a look, then both turned to my boss, who got the hint and walked to another part of the shop.

As I disrobed, I could see that the occipital area of the new threads were indeed larger, but not as crazily so as McFarlane’s delineation. I also noticed that the blue was not as deep—more toddler blue with less black in the mix—and the red was less crimson, more pink. This change may have been Marvel’s attempt at making the costume less scary to little ones or maybe Williams’s fabric supplier couldn’t match the original colors scheme. The weblines were only minimally tightened, and the spider symbol on the chest was altered to reflect McFarlane’s new design.

As I disrobed, I could see that the occipital area of the new threads were indeed larger, but not as crazily so as McFarlane’s delineation. I also noticed that the blue was not as deep—more toddler blue with less black in the mix—and the red was less crimson, more pink. This change may have been Marvel’s attempt at making the costume less scary to little ones or maybe Williams’s fabric supplier couldn’t match the original colors scheme. The weblines were only minimally tightened, and the spider symbol on the chest was altered to reflect McFarlane’s new design.Minutes later, I was in the suit. I was at once struck by the increased thickness of the fabric, which felt less giving, more resistant to movement. There was additional foot padding as well, which was not necessarily a good thing. I understood Marvel’s wanting to extend the wear on the costume’s most vulnerable area. And there may have been some consideration toward the comfort of the actor. But by increasing the padding, the tactility of the feet was decreased. When wearing a proper shoe, there is little fear of stepping on an irregular surface; the protective sole helps keep the foot in place, thus preventing an ankle rollover or even a simple moment of awkwardness. The thicker padding caused the foot to “float,” making the wearer’s footfalls less stable. When one is leaping upon tabletops or simply bounding over open terrain, the feel of one’s toes and sole is very important, especially with the suit’s limited sight. I would rather have had no padding whatsoever.

Once I had zipped up, I leaned into Williams’s face and asked, “Are my eyes straight?” I was less concerned with the symmetry of the mask than trying to get a reaction out of the unflappable Williams. No such luck.

Once I had zipped up, I leaned into Williams’s face and asked, “Are my eyes straight?” I was less concerned with the symmetry of the mask than trying to get a reaction out of the unflappable Williams. No such luck.“Fine,” she replied without flinching. “How does it feel?”

I leapt onto the work table, landing into a deep crouch with my elbows resting before me and my right arm up, hand out, striking the “Well” pose that was Jack Benny’s signature. “Seems comfortable enough,” I quipped.

For a fleeting moment, the corners of Williams mouth curled up and her mien softened. “Behave yourself,” she playfully scolded.

Though the enlarged eye area extended my peripherals, it seemed my vision was worse, as if the holes of the mesh screening that covered the eyes were smaller. I voiced my concerns to my boss, but she assured me that the fabric was unchanged. Truth be told, I’m not even sure she heard me, she was so immersed in gushing over her handiwork. I almost expected her to start exhorting, “It’s alive! Alive!!!” like Dr. Frankenstein when he noticed the slight movement of the monster’s fingers in Frankenstein. I chalked up the decreased vision of the amended suit to the gloomy conditions of the workshop. I was also told before test-piloting the new costume that the changes were essentially cosmetic, that it was just the design that was changed, not the textiles, so I let the issue drop.

It was only later when the new suit was coming off the production line and after several of the other Spider-Man actors complained that my boss admitted they had switched the fabric of the eye meshing. By then it was too late to affect the latest crop of costumes, but we were assured future orders would be constructed using the original material.

As for the public’s reaction, no one made note of the change, but the complaints of my eyes being too small were thankfully put to a halt.

10 comments:

Very interesting stories!

Familiar with your figure in the Spider-Man costume, I wonder if I have seen you as Spider-Man in the magazine called Wizard. Did you appear in that magazine many years ago by any chance? Anyway, I'm looking forward to hearing more about your wonderful experiences as Spidey. :)

Thanks, BS!

I'm sure I've appeared in Wizard over the years I was performing Spidey, never as a featured story about my exploits, though. The veteran of the Personal Appearance program, Jeremy, who was playing the Web-Slinger since the Carter administration and continued for a few years after my departure, did have an article written on his Marvel adventures in Wizard, so maybe it was he you recall.

Again thanks for the kind words. Tell your friends and keep reading!

I grew up with the Romita costume. But I remember the MacFarlane costume with fondness as well. He even did a G.I. Joe comic or two.

I believe MacFarlane started, or some of his earliest work was on, Infinity, Inc. before he started penciling Hulk shortly after Peter David's historic run began in which he returned the character to his original gray incarnation. I met him at a convention in Edmonton soon after he took over Amazing Spider-Man. Romita I saw frequently at Marvel as he was the company's art director when I was doing the Spider thang.

Thanks!

Vroom!

That's really cool! Have you seen MacFarlanes G.I. Joe work? I love everything he's done, Spidey, Hulk, Spawn, but not Joe. It just seemed...weird.

Is this Betty William's design the current one they're using for Marvel Appearances these days? I also notice that it's similar to the one they're currently using in Universal Studios Orlando...

Hi Erique!

Sorry it has taken me so long to reply.

The suit for regular appearances is probably the same design, as Spider-Man's design has remained consistent since—barring brief stints in the mechanical suit of a few years back and a short return to the black costume.

I have never had the good fortune to visit Universal's Islands of Adventure, so cannot say whether it is the same suit or not. If you emailed me a picture I would have a better idea.

Thanks for reading and taking the time to comment!

Vroom!

I recently picked up a Spider-man Costume, with a Eaves Costume label inside. The seller told me that her deceased Uncle (Jon Tanner) was a Broadway Actor in New York that was hired by the Marvel Entertainment Promotional tours in the early 1980's. I was curious if you recall ever working with him. I've really enjoyed your blog. Great stories!

This might sound like an odd question but do you know where we can buy either one of these costumes?

Great blog you hhave

Post a Comment