A couple of weeks before Thanksgiving, heroes and villains alike were convened in Hoboken at the facility where all Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade floats were designed and built. The reason: “Media Day,” a yearly event to which the press are invited for an exclusive peek at the new floats that would be unveiled that year. Well, it wasn’t quite exclusive. Macy’s always invited a local elementary school or youth organization to partake in the presentation to spice up what would otherwise be a warehouse of static constructs; still plenty interesting to Joe Average, but not the type of money shot that would get the reporters’ blood pumping. But spoon in a dollop of youngsters, mix with colorful characters, and one gets a tableau of wonderfully expressive faces guaranteed to elicit a flurry of camera shutters clicking.

In addition to sneaking a peek at the new floats as they are built, visitors are shown the steps in creating one of the parades signature giant balloons. In this case, it was the Spider-Man balloon that got the dissection. Sketches of the inflatable’s early designs are presented, after which a three-dimensional model is built. Not true to the final size, mind you. But a minute replica, about the size of a microwave oven. The preliminary concepts for the Wall-Crawler were drawn by Marvel’s Art Director and comic book legend, John Romita, who was the second delineator of the Web-Swinger’s adventures with Issue #39 back in the early 60s after inaugural artist Steve Ditko left.

John designed many of the licensed products that Marvel produced and oversaw every comic book that was published. To see the step-by-step creative breakdown Romita exercised in making the balloon a reality was thrilling for this comic geek. The cherry was seeing the model of how the genuine article was going to appear in the parade. The replica was mounted a few feet off table level with dowels attached to its underside, and a loose mock-up of a New York City street framed the model to give the spectator a sense of the real balloon scale upon completion. What an unbelievably cool collectible the miniature was—I wanted it!

To further enliven Media Day, sponsors of that year’s inaugural floats were invited to participate by supplying characters that would be featured on their floats. For example, the Children’s Television Workshop might provide Elmo or Big Bird to meet and greet the kids. Marvel furnished its entire slate of heroes and villains. It was an unusual move—a single prominent character was the norm. Let’s face it; the float sponsors certainly want the additional media attention, but the costs in entertaining a single personality—transportation for the actor and his or her costume, per diem and salary—could easily run several hundred dollars, a seemingly small amount by itself. But after spending tens of thousands of dollars on float and costume design and construction, even discounting the thousands in salary due to talent on Thanksgiving Day, an additional $500–$1000 for Media Day may be deemed too dear.

Marvel’s decision to not only participate, but also to include all thirteen of its characters, had a dual purpose: to serve as the coming out party to the New York–area media for the new live versions of its heroes and villains; and to choreograph the fight scene that was to be performed on the float on national television in front of Macy’s during the parade. Ever the frugal company not wanting to pay the costs involved in making an additional stop to the facility for the sole purpose of staging the fight scene, Marvel combined everything. Thus, all the actors were shuttled over from the main office early enough that morning so that the choreography would be complete before the kids and press arrived.

It was also of utmost importance for us to acclimate ourselves with the landscape of the float—our stage, as it were—and subsequently determine what we’d be able to do or not do when in costume. This would figure into the final choreography and lead to any construction adjustments to the float or costumes.

This was the first time any of us had seen the float on which we would be performing, and “wide-eyed” and “agape” would certainly be two words one witnessing our reaction could use. The float was huge—24 feet long—towering in parts—just more than three stories at its highest point. It looked as if it were designed by an architect with Attention Deficit Syndrome: a skyscraper mashed up with a steel-girdered construction site, hugging Doctor Strange’s Sanctum Sanctorum, pressed against a bell tower, which sat atop a dungeon. Worked into the multi-level design were poles, bars, ladders, open windows, staircases, and access ways of every sort, so the characters could climb, shimmy, swing, slide, and traverse the compressed cityscape with ease.

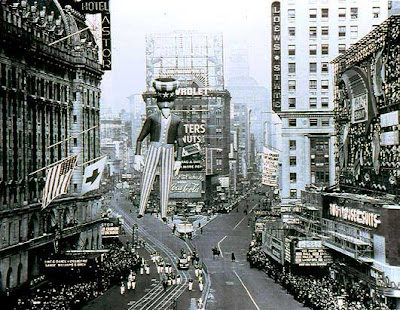

The Marvel Universe float (Notice Silver Surfer on his surfboard 32-feet above street-level atop the rear skyscraper)

The Marvel Universe float (Notice Silver Surfer on his surfboard 32-feet above street-level atop the rear skyscraper) I was mesmerized. As the friendless child of a dysfunctional broken home, play-sets were my preferred escape. One of my earliest was a wooden fort. It measured approximately three-feet square and a foot high, and was constructed by inmates at Walpole Prison in Massachusetts. There was the World War II set that featured army-green American soldiers and blue-grey Nazis (some even goose-stepping!); faux plastic barbed wire; a pillbox which, even as a child, I knew was the enemy’s bailiwick and always the toughest part to conquer; and two cannons—one of German, the other of American design—that actually fired shells. The set also included a fold-out plastic terrain of the same quality as self-sticking window decorations. I never used it, because it would not flatten completely, making it nigh-impossible to get the soldiers to stand. I’d separate both sides with barbed wire, then take turns crawling from the good guys’ to the bad guys’ side lining up the cannons and firing. The last-soldier-standing’s side won. Then there was the historically inaccurate dawn-of-man set that combined cave men with dinosaurs. I even had a Planet of the Apes set that consisted of gorilla warriors, humans and two trees between which was a hung a plastic rope bridge. I spent hours with my play-sets, blocking adventures worthy of Steven Spielberg.

The Marvel float was a play-set writ large. And my fellow character actors and I were the action figures!

Bookending the miniature skyscraper at the very back of the float were mega-sized comic books made of large flat sheets of plywood. The covers and interiors were recreated from actual Marvel comics—I remember one clearly showing Spider-Man battling the Scorpion inspired by a Gil Kane cover from the 1970s. Each contained a mere handful of pages, but each page was fully-painted in the primary-color palette indicative of “funny Books,” complete with word balloons, though chicken scratches were used to emulate actual words. From a couple of feet the artwork may have looked rough, but from a spectator’s viewpoint, it was as if New York City was Lilliput and Gulliver himself had brought these issues with him from his personal collection at home. And if you were a comic geek, they were the coolest… things… ever.

Bookending the miniature skyscraper at the very back of the float were mega-sized comic books made of large flat sheets of plywood. The covers and interiors were recreated from actual Marvel comics—I remember one clearly showing Spider-Man battling the Scorpion inspired by a Gil Kane cover from the 1970s. Each contained a mere handful of pages, but each page was fully-painted in the primary-color palette indicative of “funny Books,” complete with word balloons, though chicken scratches were used to emulate actual words. From a couple of feet the artwork may have looked rough, but from a spectator’s viewpoint, it was as if New York City was Lilliput and Gulliver himself had brought these issues with him from his personal collection at home. And if you were a comic geek, they were the coolest… things… ever.We learned the bell tower was collapsible, it’s climactic destruction coming at the hands of the Hulk. How the Hulk would be able to climb into position and whether he’d be able to actually topple the tower while in costume were two concerns. Another: where could the Hulk performer, Mark, take sorely needed breaks during the parade. Even if the temperature were to be unseasonably cold on Thanksgiving day, it would have little effect in relieving Mark of the smothering heat within the Hulk costume. The general rule when playing the character was twenty minutes in, twenty minutes out. The anticipated time from start to stop before Macy’s for the fight sequence was an hour. Mark would need at least a few breaks within that timeframe, including a crucial one just before the battle.

There was even an elevator—at least by the strictest definition of the term—a platform that moved approximately three feet (if that) from the roof of the second tallest structure to the roof of the building it abutted against. But the distance could more easily be gained with one long step and a wee bit of effort. And it was slow. The wheelchair lifts on public buses seem a blur in comparison.

Though a portable version of his board was constructed for personal appearances, The Silver Surfer would not be expected to carry it with him during the parade. Atop the thirty-two-foot skyscraper looming from the back end, a replica of the surfboard was secured. It jutted out like the gang plank of a pirate ship and would be the Surfer’s perch as the float lurched along the parade route. The only way to attain this precarious position was by shimmying up two parallel vertical poles affixed to the backside of the building. It would also be the only means of descent. The location and means of access to the board were two particulars Jim, the Silver Surfer actor, was not made aware of before seeing the float. What if he were afraid of heights? While in costume, would he even be able to shimmy thirty feet to get into starting position or down for the big battle, never mind doing so while the float was actually lumbering down the parade route? More importantly, how was he going to keep from tumbling off his perch? Though well-built from plywood and two-by-fours and securely fitted to the float’s frame, the skyscraper would sway according to the vagaries of the street’s surface and New York is famous for its potholes. Plus, as his board was a good ten feet above the adjoining girders of the faux construction site built beside his skyscraper, the Surfer would be exposed to the cold and wind that would surely be blowing the day of the event, further raising the danger level of his mise en place.

We were allowed, nay encouraged, to explore the float, not that it took much coaxing. Most of the actors took to the directive like children being told to test out new playground equipment. The performer who would be playing Powerman was less enthusiastic. I immediately suspected that he wasn’t an actor at all, but a body-builder. He was extremely muscular in that Schwarzenegger way, which perfectly suited the character, and amiable enough, but most wallpaper has a more animated personality. His movements across the float said more “I was paid to wear a costume and wave, not take part in any athletic activities,” rather than “This is going to be so cool for my character!” I wondered at the time if he was going to shave his thick black mustache—Luke Cage, a.k.a Power Man, was clean-shaven in the comics. Our performer’s mustache made him look like Richard Roundtree after swallowing Arnold Schwarzenegger! It would have been advisable for him to shave it regardless of the roll. But I certainly wasn’t going to tell him!

We were allowed, nay encouraged, to explore the float, not that it took much coaxing. Most of the actors took to the directive like children being told to test out new playground equipment. The performer who would be playing Powerman was less enthusiastic. I immediately suspected that he wasn’t an actor at all, but a body-builder. He was extremely muscular in that Schwarzenegger way, which perfectly suited the character, and amiable enough, but most wallpaper has a more animated personality. His movements across the float said more “I was paid to wear a costume and wave, not take part in any athletic activities,” rather than “This is going to be so cool for my character!” I wondered at the time if he was going to shave his thick black mustache—Luke Cage, a.k.a Power Man, was clean-shaven in the comics. Our performer’s mustache made him look like Richard Roundtree after swallowing Arnold Schwarzenegger! It would have been advisable for him to shave it regardless of the roll. But I certainly wasn’t going to tell him!Surfer Jim shimmied up the skyscraper like God meant for him to have been a chimpanzee, but forgot to make the necessary 2% changes to his DNA. Once at the peak, he could have thanked God personally for making the mistake. Us lowly groundlings got nervous just looking up at him with nought but a narrow plank on which to stand. Mark, a.k.a. Captain America—not to be confused with Hulk-Mark—scurried up the skyscraper just as easily. He and Jim looked like two playful squirrels chasing one another. That kind of climbing was not something I was ever able to do; I needed hand- and footholds. Though I suspected climbing ability would be a moot issue for the guy wearing the iron diaper.

The suspicions proved prescient when, after everyone had donned his or her costumes, we were once again let loose to explore the float. I could barely walk without emulating Festus on Gunsmoke. Amazingly, whatever limitations either the Silver Surfer or Captain America suits had were lost on Jim and Mark, who darted up the skyscraper with ease—the Surfer, sporting his Caspar head and wearing sparkly gloves and dance shoes, like he were rehearsing a Bob Fosse number; and Cap, bedecked in red-leather gloves and boots, with a circular shield strapped to his back. Jim did profess some slippage with his Michael Jackson gloves, a problem solved with patches of leather later sewn into the palms.

The suspicions proved prescient when, after everyone had donned his or her costumes, we were once again let loose to explore the float. I could barely walk without emulating Festus on Gunsmoke. Amazingly, whatever limitations either the Silver Surfer or Captain America suits had were lost on Jim and Mark, who darted up the skyscraper with ease—the Surfer, sporting his Caspar head and wearing sparkly gloves and dance shoes, like he were rehearsing a Bob Fosse number; and Cap, bedecked in red-leather gloves and boots, with a circular shield strapped to his back. Jim did profess some slippage with his Michael Jackson gloves, a problem solved with patches of leather later sewn into the palms.The choreographer, Bill Guskey, was familiar with the limitations of costumed characters and how to “cheat” those limitations to fullest effect. Even without that knowledge, it was quickly apparent to the actors that he knew his stuff. Bill asked our comfort-level before committing a sequence to the choreography, deconstructing whole sections unhesitatingly and adjusting with on-the-spot changes that proved equally exciting. He allowed plenty of time for movement—understanding the sight restrictions inherent, especially with the bulkier costumes like mine and the Hulk’s—adding dramatic flourishes to conceal the delayed movement, which only served the traditionally melodramatic nature of superheroic adventures.

And Bill was sensitive to the needs of the client. Every character got face time, no matter how scant. After all, Marvel paid tens of thousands of dollars on this parade among the Spider-Man balloon, float, costumes, choreography and actor fees. Making sure every character was prominently displayed on national television was key. Bill even worked in RoboCop without making the oddness of the character’s presence too pronounced. Unfortunately, Iron Man’s role was in the “scant” column. With my extremely hampered mobility and sight, I couldn’t take a more active role with risking my ability to have children later in life.

Fortunately, it was discovered that there was enough space within the bell tower for Hulk-Mark to take breaks—which entailed removing his head and hands off to allow his body to cool off and breathe—without being seen from the onlookers along the parade route. He’d also be perfectly placed for the grand finale of the battle. As long as he remembered to get into costume on the bell tower before the parade started, the Hulk was good to go. But for the kiddies later in the day, Hulk-Mark would be playing the part of the Green Goblin. There just wasn’t a convenient spot for him to change into the Hulk at the Macy’s float facility.

Hulk-Mark took to the change as if he’d been freed from years of incarceration. When the children arrived he taunted them and cackled with an insane glee, scurrying up and down the bars and poles of the float like a mountain goat. The kids loved it and shouted right back at him. I was laughing so hard, I momentarily forgot about the pain of the hard celastic digging into my groin area every time I moved. Something would have to be done before we next convened, which would be the Wednesday evening before Thanksgiving.

NEXT: Oily to Bed, Oily to Rise