If you are anywhere near Manhattan in the next several weeks, creep, crawl, lurch, or better yet, run as if some unspeakable horror is chasing you, to the Tim Burton exhibit at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Burton is a filmmaker (Beetlejuice, Batman, Willy Wonka, Sweeney Todd, etc.) the type whose distinctive touch is instantly discernable in everything he creates. Much like the films of Terry Gilliam, the Coen brothers or Hal Hartley, one cannot help but know they are watching a Burton flick.

If you are anywhere near Manhattan in the next several weeks, creep, crawl, lurch, or better yet, run as if some unspeakable horror is chasing you, to the Tim Burton exhibit at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Burton is a filmmaker (Beetlejuice, Batman, Willy Wonka, Sweeney Todd, etc.) the type whose distinctive touch is instantly discernable in everything he creates. Much like the films of Terry Gilliam, the Coen brothers or Hal Hartley, one cannot help but know they are watching a Burton flick.What many may not realize is that Burton is also an artist. But it won’t take long for anyone experiencing the MoMA exhibit to see that Burton’s talent in the visual arts is as masterful as that in his filmmaking.

NOTE: Get your tickets in advance; most days sell-out long beforehand.

I had seen some of Burton’s preliminary sketches for various films, such as Nightmare Before Christmas, and those he provided for

Melancholy Death of Oyster Boy and Other Stories, his short story collection that was released a few year ago. But I expected more of the exhibit to focus on the former—along with props and costumes from his movies—than the latter, less commercial work.

Melancholy Death of Oyster Boy and Other Stories, his short story collection that was released a few year ago. But I expected more of the exhibit to focus on the former—along with props and costumes from his movies—than the latter, less commercial work.I was happily surprised.

Sure, there are cases filled with puppets from the aforementioned Nightmare and his other stop-motion feature, Corpse Bride; props, such as the heads of Sarah Jessica Parker’s and Pierce Brosnan’s characters in Mars Attacks!; and costumes, including the cape worn by the headless horseman in Sleepy Hollow. But there are also hundreds of drawings and paintings, beyond those done for his movie work, from throughout his life.

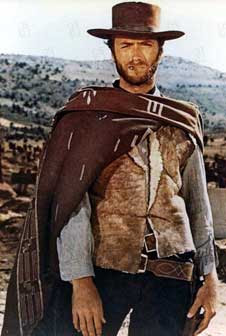

Notice the fine line work and economy of color in this storyboard panel from Nightmare Before Christmas

Notice the fine line work and economy of color in this storyboard panel from Nightmare Before ChristmasBurton’s art is extraordinary; his line work—the control and wherewithal of such—had me shaking my head in profound disbelief. Even in his most lackadaisical of doodles, one can see genius. It’s no wonder he won a scholarship to the prestigious CalArts, the fine arts institution founded by Walt and Roy Disney, when he was eighteen.

Artists Gahan Wilson, Edward Gorey and MAD magazine were clear influences in both subject matter and technique. And Burton’s signature twisted, subversive humor is evident in his

earliest pieces. I especially liked “Man Undressing a Woman with His Eyes,” the three-drawing sequence of a couple meeting at a party, “Man with Permanent Seeing Eye Dogs,” and “Little Dead Riding Hood,” but there are many others that tickled me.

earliest pieces. I especially liked “Man Undressing a Woman with His Eyes,” the three-drawing sequence of a couple meeting at a party, “Man with Permanent Seeing Eye Dogs,” and “Little Dead Riding Hood,” but there are many others that tickled me.Pablo Picasso once said that he spent his whole life learning how to draw like a child; to create with a mind free of preconception, prejudice, rule or life-experience. Burton’s art is a testament to this belief. His work is fearless, boundless, unfettered by convention. I was as awe-struck as I was jealous of his facility to just draw whatever comes to his mind; not think before putting instrument to paper.

Accompanying some of Burton’s one-dimensional creations are maquettes by model maker Rick Heinrichs. And there are also a few “life-size” statues of his dark visions. All add to the exhibit’s enjoyment.

Unfortunately, the space MoMA provides for the exhibit is too limited—two small rooms. Most McDonald’s restaurants provide more space for their customers. Burton’s numerous drawings are crowded on the walls like the celebrity photos at Sardi’s. Alcoves the size of half-baths featuring screens on which the filmmaker’s early animated work played, were pigeon-holed in the exhibit like an afterthought. Unsurprisingly, museum-goers stopped—many even sat—before the screens to watch, creating immovable

Unfortunately, the space MoMA provides for the exhibit is too limited—two small rooms. Most McDonald’s restaurants provide more space for their customers. Burton’s numerous drawings are crowded on the walls like the celebrity photos at Sardi’s. Alcoves the size of half-baths featuring screens on which the filmmaker’s early animated work played, were pigeon-holed in the exhibit like an afterthought. Unsurprisingly, museum-goers stopped—many even sat—before the screens to watch, creating immovable  areas of traffic. I would have liked to enjoy them myself, but the set-up was not conducive to doing so. Other screens hung among the scads of art further impeding the flow of the patrons. And the exhibit was PACKED. I was among the first day’s group to enter and the space filled in minutes and only got worse as each successive scheduled ticket group’s time opened up.

areas of traffic. I would have liked to enjoy them myself, but the set-up was not conducive to doing so. Other screens hung among the scads of art further impeding the flow of the patrons. And the exhibit was PACKED. I was among the first day’s group to enter and the space filled in minutes and only got worse as each successive scheduled ticket group’s time opened up.What was the museum thinking? That an exhibit featuring the work of one of the world’s most popular visionary’s, in the country’s most populated—not including the millions of tourists that visit everyday—cities, wouldn’t be busy?!! I’d hate to think the decision was prejudiced, that the MoMA nabobs responsible for such decisions didn’t feel Burton’s work worthy of more space. As much as I enjoyed the work, the overall experience was hot, uncomfortable and completely AVOIDABLE had the exhibit been given the space it deserved.

Fortunately, MoMA’s website freely provides many, if not all, of the pieces featured in the exhibit, including the video segments. It’s not the same as seeing the art live, but at least your not getting jostled about or intimidated to move away from any piece you’d prefer to linger over.

Tim Burton’s work gets the full five spiders.

The exhibit gets a woeful two and a half spiders (the extra half a result of the museum’s website coverage of the exhibit)!

The exhibit gets a woeful two and a half spiders (the extra half a result of the museum’s website coverage of the exhibit)!