I should have expected something unusual by the peculiar lilt in Wolverine’s voice when he introduced me to his little friend…

Wolverine, Captain America and I—Spider-Man—were appearing at the University Mall in Tampa, FL. Most often, appearances at malls would occur in a particular store and usually included one hero, two tops. But this was a major promotional event mounted by the mall itself with a budget to match, so three Marvel powerhouses were recruited.

Still, the mall tried to recoup some of its investment by offering Polaroids at $3 a shot to any fan who so desired one. That’s a buck a hero (Hell, put us in the 99¢ store!) Of course, no purchase was necessary to meet the heroes and get their autographs and to that end Marvel supplied “Marvel Fun & Games” booklets to the cause.

What, no comic books?!! I thought comics were provided to clients for signings...

When I began my web-slinging career, that was the case. Upon booking an appearance, Babs, my boss, would fill out the appropriate forms with the newsstand sales department, who would then feed the request into the system and, Voilà!, comic books arrived at the desired location from the nearest newsstand distributor. The exception was with gigs at comic book stores. As a means to support these keepers of the flame, as it were, who constantly struggled in an ever shrinking market, Marvel’s Personal Appearance Department offered comic shops a friendlier rate, only sans free comics. This makes perfect sense. After all, they are a comic book shop. Giving away that in which they specialize can only serve to hinder those additional sales expected from having a superhero at the store in the first place. This isn’t to say that retailers never gave away free books at gigs. Some certainly did, seeing the event as a means to get publicity and attract customers—parents and their kids—who wouldn’t normally set foot in such an establishment.

But for conventional jobs, a free allotment of comics was S.O.P. Unfortunately, on occasion, the comics never arrived or not in time, which is just as bad. Savvy clients took the clip art of the characters that Marvel also provided with every gig and designed and printed flyers the children could color as back-up; not nearly as cool as receiving a comic book, but better than nothing. Then there were the rare instances when relieved clients received the comics promptly only to discover, when they opened the box, that there were DC comics—Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, etc.—inside (Oops! Talk about shooting yourself in the foot.).

Of course, as the only representative of the company on site and the most iconic/famous, Spidey would be the one disgruntled customers approached. (Why me? You’d think Captain America would be the go-to guy, being a captain and all, not to mention the leader of the Avengers, “Earth’s Mightiest Heroes.” I can understand not confronting the Hulk. No one likes him when he’s angry. But moi?!! I’m a menace to society, the source of all New York City’s ills, according to the Daily Bugle, that is. Don’t these people read the books? Sheesh!)

Of course, as the only representative of the company on site and the most iconic/famous, Spidey would be the one disgruntled customers approached. (Why me? You’d think Captain America would be the go-to guy, being a captain and all, not to mention the leader of the Avengers, “Earth’s Mightiest Heroes.” I can understand not confronting the Hulk. No one likes him when he’s angry. But moi?!! I’m a menace to society, the source of all New York City’s ills, according to the Daily Bugle, that is. Don’t these people read the books? Sheesh!)“Where are the comics?” the one-in-charge would pointedly ask. Like I’d be lugging fifty-plus pounds of funny books with me on the trip from New York.

“They should have been delivered,” I’d offer.

“Well, they haven’t. Now, I have nothing to give the kids.”

If I’d thought for a moment that this invective was a result of the person’s concern for the children’s feelings, I might have sympathized. But it was nothing more than a person worried about covering their ass and staving off a reprimand from their boss. This is not to say I wasn’t concerned about the feelings of my constituents. Au contraire, absence of free comics or flyers only upped the ante on my performance. I felt that I needed to work even harder to entertain the troops.

By ’91, the year of the Tampa appearance (No, I haven’t forgotten… thanks for sticking around…), Marvel’s Personal Appearance Department replaced free comic books with “Marvel Fun & Games” booklets. The idea was to create something that the department could easily and cheaply—comic books are heavy and thus expensive to ship—send directly from the office, circumnavigating a middleman/distributor. Also, the booklets were compact enough that the actors could carry a few hundred of them to every gig as back-up, in case the main shipment didn’t arrive.

By ’91, the year of the Tampa appearance (No, I haven’t forgotten… thanks for sticking around…), Marvel’s Personal Appearance Department replaced free comic books with “Marvel Fun & Games” booklets. The idea was to create something that the department could easily and cheaply—comic books are heavy and thus expensive to ship—send directly from the office, circumnavigating a middleman/distributor. Also, the booklets were compact enough that the actors could carry a few hundred of them to every gig as back-up, in case the main shipment didn’t arrive.Though I recognized the problem and applauded Marvel’s intent, the result was lacking. The “Marvel Fun & Games” booklet was nothing more than a single, black-and-white, double-sided, sheet (Big whoop!) that was folded once, and contained Marvel superhero-themed puzzles and character illustrations. I hated them! Besides looking cheap—they weren’t even in color—as a marketing tool they did nothing to draw people to the comics, thus increasing sales, which is the whole point of promotional giveaways.

The booklets lasted about as long as Furbys did, replaced by exclusive personal-appearance trading cards. Still, not a great freebie for selling comic books—trading cards, maybe, but not comics—but a lot cooler. I’d like to think it was my thoughtful, diplomatically-presented argument (read: bitching) against the puzzle “brochures,” that led to their demise, but modesty prevents me from taking credit.

The booklets lasted about as long as Furbys did, replaced by exclusive personal-appearance trading cards. Still, not a great freebie for selling comic books—trading cards, maybe, but not comics—but a lot cooler. I’d like to think it was my thoughtful, diplomatically-presented argument (read: bitching) against the puzzle “brochures,” that led to their demise, but modesty prevents me from taking credit.As for those lackluster puzzle-pamphlets and the University Mall event…

I would have hated having to tell a child that they couldn’t receive a photograph featuring them with their favorite superheroes unless they forked over some dough (So sorry, but here’s a piece of paper with some black-and-white pictures of us on it, instead... Thanks for playing!). I realize children love getting something… anything from Spider-Man and his pals, but when they

see other children getting a full-color live photo of themselves with the superheroes, it’s like the scene in It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown when, while trick-or-treating, all the other kids get candy and Charlie Brown gets a rock. Fortunately, two comely young lasses were provided to collect money, operate the camera, keep order in the line… and gracefully say to anyone unwilling to pay, “No ticky, no laundry!”

see other children getting a full-color live photo of themselves with the superheroes, it’s like the scene in It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown when, while trick-or-treating, all the other kids get candy and Charlie Brown gets a rock. Fortunately, two comely young lasses were provided to collect money, operate the camera, keep order in the line… and gracefully say to anyone unwilling to pay, “No ticky, no laundry!”The event took place at the center court area of the mall. It was a beautiful day, and skylights overhead allowed the sun to keep the area bright… and toasty. I certainly didn’t mind. If you’ve ever been to the Sunshine State, you know that Floridian retailers keep the air-conditioning level so high, you could store carcasses in the aisles for several weeks without their spoiling. I was quite comfortable; not so for Wolvie and Cap.

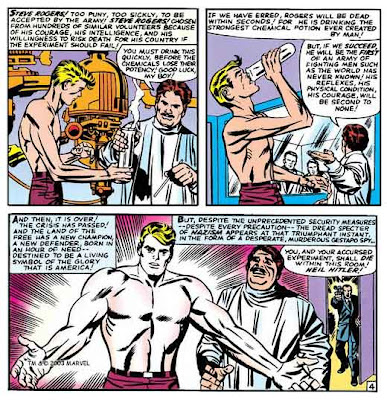

Although originally designed to be worn without an underlying muscle-suit, the Captain America costume was later incorporated with one to reflect the growing testosterone level of the character in the comics. Cap was always fit, but never a cement-head. He was a product of a “secret soldier serum,” designed by the American military, which prospective soldier, Steve Rogers, agreed to take as his way to help fight the Germans during World War II after he was deemed too frail for regular service. The serum made Rogers super-fit, but not grotesquely bulky, like the Hulk, and greatly enhanced his athleticism. Thus, Marvel hired able-bodied actors, not bodybuilders, for the role.

Wolverine, in contrast, was a “brick shithouse,” as my mother used to say: squat—technically five' four", according to the comics—square and all muscle, so Marvel decided it would be easier to have the actor playing the feisty Canuck wear a muscle-suit beneath the outer-lying spandex than to find men with the proper physique who could also act. Of course, this resulted in the Captain America actors looking scrawny in comparison, so they were subsequently forced to accompany the red-white-and-blue threads with a muscle-suit. The Captain Americas were ordinarily hot in the nearly all-encompassing costumes, but adding a muscle suit to the mix, increased the discomfort tenfold—the Wolvies were already at that level. Add a copious amount of sunshine and the two heroes were sweating more than Perez Hilton eating a corn dog (Take a look at the pit stain on Wolverine in the pic below, if you do not believe me. And that is through thick padding!).

Wolverine, in contrast, was a “brick shithouse,” as my mother used to say: squat—technically five' four", according to the comics—square and all muscle, so Marvel decided it would be easier to have the actor playing the feisty Canuck wear a muscle-suit beneath the outer-lying spandex than to find men with the proper physique who could also act. Of course, this resulted in the Captain America actors looking scrawny in comparison, so they were subsequently forced to accompany the red-white-and-blue threads with a muscle-suit. The Captain Americas were ordinarily hot in the nearly all-encompassing costumes, but adding a muscle suit to the mix, increased the discomfort tenfold—the Wolvies were already at that level. Add a copious amount of sunshine and the two heroes were sweating more than Perez Hilton eating a corn dog (Take a look at the pit stain on Wolverine in the pic below, if you do not believe me. And that is through thick padding!).Spider-Man, aka Peter Parker, was always just a puny nerd, who received the proportional strength of a spider when bitten by a radioactive arachnid, but remained small, albeit more wiry by virtue of web-swinging and fighting crime. Ergo, a muscle-suit never became a staple of the Spidey suit. It would make crouching, perching, leaping and contorting—the signature movements of the character—impossible.

Another drawback of the Wolverine costume was the decreased ability to hear caused by the headpiece. To achieve the recognized look of opposing vertical projections arising from the sides of his head—a look not too dissimilar to Batman’s cowl—in such a way as to retain its structure and not sag, the designer created a hard, molded form over which fabric was stretched. Though not negating the wearer’s hearing outright, it greatly reduced it.

Contrarily, I found my hearing noticeably augmented when in the Spider-Man suit. My theory: the reduction of my sight by the white screening over my eyes caused my remaining senses to compensate. I’d find myself overhearing parents in line talking with their kids about what they were going to ask Spidey when it was their turn, while I was in the midst of autographing for another child. The look on their wee faces when I greeted them by name or brought up a nugget of info from the discussion with their parents was priceless… as was the disturbed look on Mom’s and Dad’s face as they worriedly pondered who was this strange man in the Spider-Man suit who knows their child so well.

Wolverine’s limited aural abilities and my enhanced ones begat one of my fondest Spider-Man memories, which occurred moments before the titular X-Man’s suspicious introduction which opened this posting. As could be expected, the appearance of three beloved superhero icons in the center court of Tampa’s most popular mall on a Saturday afternoon elicited quite a turnout. Greet-pose-sign-adieu-repeat became the day’s drill for Cap, Wolvie and I, with sporadic periods of straightforward signing for those children in line for an autograph and not a picture. It was during one of these signing sessions that I overheard through the hubbub the following short exchange between Wolverine and a young child of no more than four, who was obviously confused about the hero’s similarity to a certain caped crusader:

Boy: “Are you Batman?”

Wolverine: “No I’m a good man.”

The innocence of the lad’s inquiry; Wolverine’s mistaken response delivered with quiet, heartfelt reassurance, believing the lad was terrified, having asked him if he was a “bad man,” then the boy’s confused look after Wolvie’s answer… Priceless.

I, of course, being the sympathetic and supportive team player for which I am often revered, produced an enthusiastic guffaw. “Hey, Wolvie… You may want to get your ears checked. He was asking if you were Batman. You know, caped crusader, Gotham City vigilante…?”

All Wolvie could do is watch as the boy shuffled toward me, all the while looking over his shoulder at Wolverine with a look that said, This is the kind of person my mommy warned me about. Children can be so unforgiving.

All Wolvie could do is watch as the boy shuffled toward me, all the while looking over his shoulder at Wolverine with a look that said, This is the kind of person my mommy warned me about. Children can be so unforgiving.Before the end of the day Wolverine got his revenge. As mentioned, the twinkle in his voice should have tipped me off, never mind his more than normal personal attention to introducing to me the little boy in question.

“Hey, Spider-Man, this is my friend…” and then he said the child’s name, which sounded like lay-MON-zhel-low (the zh pronounce like the soft French g in Gigi). This was unique even to me after five years and thousands of personalized autographs. It sounded Spanish or Portuguese and had a notable flair. I told the lad how cool I thought his name was, then dutifully asked him its spelling as I signed his “Marvel Fun & Games” booklet.

“L-E-M-O-N-J-E—” he carefully began.

“THAT’S LEMON JELL-O!” I incredulously blurted before the boy could utter the final O.

“My mom likes Jell-O,” he offered in a defeated tone.

“I love Jell-O!” My quick recovery seemed to enlighten the child and spur his twin brother, who I hadn’t noticed behind him …

“And I’m (or-RON-zhel-low)!

You guessed it: his brother’s name was spelled Orangejello!

It boggled my mind that a parent would do that to their children. Kids have a hellacious time growing up as it is without having to fend off the additional abuse sure to come from being named after a gelatinous confection made from animal hooves.

Upon reflection I cannot help but think that I’d dodged a bullet. My mom loved pickled pigs’ feet!